“底层年代学所揭示的秘密”《欧洲第一个千年到底有多长?》(二·五)

“底层年代学所揭示的秘密”《欧洲第一个千年到底有多长?》(二·五)

How Long Was the First Millennium?

译文简介

海因索恩的工作不容易总结,因为它是一项正在进行的工作,因为它几乎涵盖了全球所有地区,因为它有大量的插图,并与历史和考古研究相佐证。

正文翻译

Heinsohn’s work is not easy to summarize, because it is a work in progress, because it covers virtually all regions of the globe, and because it is abundantly illustrated and referenced with historical and archeological studies. Nothing can replace a painstaking study of his articles, completed with personal research. All I can do here is try to reflect the scope and the depth of his research and the significance of his conclusions. Rather than paraphrase him, I will quote extensively from his articles. From now on, only quotations from other authors will be indented. All illustrations, except the next one and the last one, are borrowed or adapted from his articles.

海因索恩的工作不容易总结,因为它是一项正在进行的工作,因为它几乎涵盖了全球所有地区,因为它有大量的插图,并与历史和考古研究相佐证。没有什么能代替对他的文章的潜心研究,并辅以个人研究。

我在这里所能做的就是尽量反映出他的研究的广度和深度,以及他的结论的重要性。我将广泛地引用他的文章,而不是转述他的话。从现在起,只有来自其他作者的引文才会单独分段。所有的插图,除了下一个和最后一个,都是借用或改编自他的文章。

海因索恩的工作不容易总结,因为它是一项正在进行的工作,因为它几乎涵盖了全球所有地区,因为它有大量的插图,并与历史和考古研究相佐证。没有什么能代替对他的文章的潜心研究,并辅以个人研究。

我在这里所能做的就是尽量反映出他的研究的广度和深度,以及他的结论的重要性。我将广泛地引用他的文章,而不是转述他的话。从现在起,只有来自其他作者的引文才会单独分段。所有的插图,除了下一个和最后一个,都是借用或改编自他的文章。

The best starting point is his own summary (“Heinsohn in a nutshell”): “According to mainstream chronology, major European cities should exhibit — separated by traces of crisis and destruction — distinct building strata groups for the three urban periods of some 230 years that are unquestionably built in Roman styles with Roman materials and technologies (Antiquity/A>Late Antiquity/LA>Early Middle Ages/EMA). None of the ca. 2,500 Roman cities known so far has the expected three strata groups super-imposed on each other. … Any city (covering, at least, the periods from Antiquity to the High Middle Ages [HMA; 10th/11th c.]) has just one (A or LA or EMA) distinct building strata group in Roman format (with, of course, internal evolution, repairs etc.).

最好的起点是他自己的总结(“海因索恩的概括”):

“根据主流年表,欧洲主要城市应该在230年左右的三个城市时期中(古代-古代晚期-中世纪早期),展示出不同的建筑地层群,这些建筑无疑是用罗马风格、罗马材料和技术建造的。到目前为止,已知的大约2500座罗马城市中,没有一座是预期的三个时期相互叠加的。

任何一座城市(至少从古代到中世纪中期(10-11世纪)),都只有一种罗马范式的独特的建筑地层群(毫无疑问,包括内部演进、修复等)。

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

最好的起点是他自己的总结(“海因索恩的概括”):

“根据主流年表,欧洲主要城市应该在230年左右的三个城市时期中(古代-古代晚期-中世纪早期),展示出不同的建筑地层群,这些建筑无疑是用罗马风格、罗马材料和技术建造的。到目前为止,已知的大约2500座罗马城市中,没有一座是预期的三个时期相互叠加的。

任何一座城市(至少从古代到中世纪中期(10-11世纪)),都只有一种罗马范式的独特的建筑地层群(毫无疑问,包括内部演进、修复等)。

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

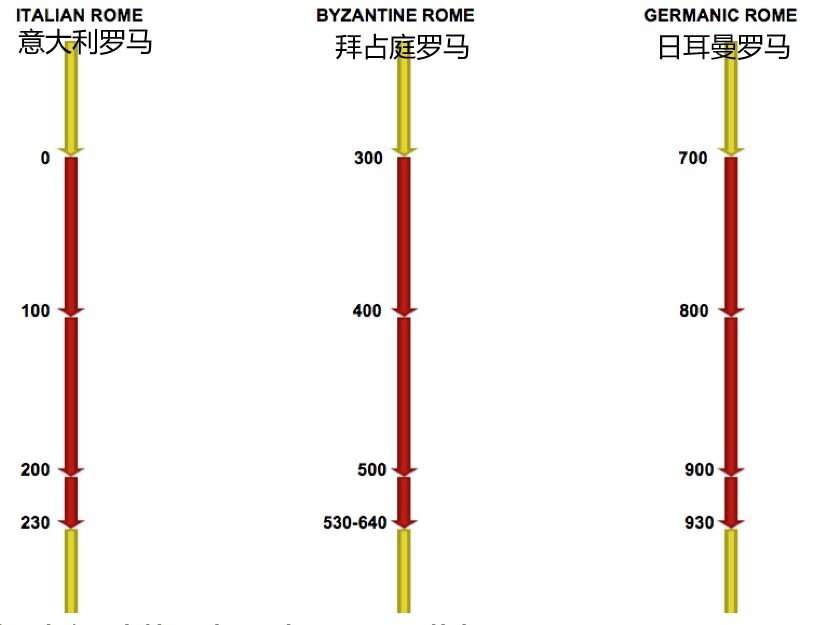

Therefore, all three urban realms labeled as A or LA or EMA existed simultaneously, side by side in the Imperium Romanum. None can be dexed. All three realms (if their cities continue at all) enter HMA in tandem, i.e. all belong to the 700-930s period that ended in a global catastrophe. This parallelity not only explains the mind-boggling absence of technological and archaeological evolution over 700 years but also solves the enigma of Latin’s linguistic petrification between the 1st/2nd and 8th/9th c. CE. Both text groups are contemporary.”

因此,这三个被标记为“古代”或“古代晚期”或“中世纪早期”的城市领域同时存在,并排存在于罗马帝国中。都不能无视。这三个时期(如果它们的城市继续存在的话)同时进入“中世纪中期”,也就是说,它们都属于以全球灾难告终的700-930年代。

这种相似性不仅解释了700多年来令人难以置信的技术和考古进化的缺失,而且还解决了公元1-2至8-9世纪拉丁语语言僵化的谜团。

(换句话说,)这两样东西都是当代的。”

因此,这三个被标记为“古代”或“古代晚期”或“中世纪早期”的城市领域同时存在,并排存在于罗马帝国中。都不能无视。这三个时期(如果它们的城市继续存在的话)同时进入“中世纪中期”,也就是说,它们都属于以全球灾难告终的700-930年代。

这种相似性不仅解释了700多年来令人难以置信的技术和考古进化的缺失,而且还解决了公元1-2至8-9世纪拉丁语语言僵化的谜团。

(换句话说,)这两样东西都是当代的。”

In other words, from other articles: “The High Middle Ages, beginning after the 930s A.D., are not only found –– as would be expected –– contingent with, i.e., immediately above the Early Middle Ages (ending in the 930s). They are also found –– which is chronologically perplexing –– directly above Imperial Antiquity or Late Antiquity in locations where settlements continued after the 930s cataclysm.”[9] “There is — in any individual site — only one period of some 230 years (all of them with Roman characteristics, such as imperial coins, fibulae, millefiori glass beads, villae rusticae etc.) that is terminated by a catastrophic conflagration.

换句话说,从其他文章中可以看出:“公元930年代以后开始的中世纪中期,不仅如人们所预料的那样,与早期中世纪(结束于930年代)紧密相连。它们也被发现这在年代上是令人困惑的,因为就在帝国古代或晚期古代的正上方,在930年代大灾难之后,定居点仍在继续。”

“在任何单独的遗址中,只有一个大约230年的时期(所有这些时期都具有罗马的特征,如帝国硬币、fibulae、千花玻璃珠、乡村等)被一场灾难性的大火所终结。”

换句话说,从其他文章中可以看出:“公元930年代以后开始的中世纪中期,不仅如人们所预料的那样,与早期中世纪(结束于930年代)紧密相连。它们也被发现这在年代上是令人困惑的,因为就在帝国古代或晚期古代的正上方,在930年代大灾难之后,定居点仍在继续。”

“在任何单独的遗址中,只有一个大约230年的时期(所有这些时期都具有罗马的特征,如帝国硬币、fibulae、千花玻璃珠、乡村等)被一场灾难性的大火所终结。”

Since the cataclysm dated to the 230s shares the same stratigraphic depth as the cataclysms dated to the 530s or the 930s, some 700 years of 1st millennium history are phantom years.” The first millennium, in other words, lasted only about 300 years. “Following stratigraphy, all earlier dates have to come about 700 years closer to the present, too. Thus, the last century of Late Latène (100 to 1 BCE), moves to around 600 to 700 CE.”

由于230年代的大灾难与530年代或930年代的大灾难具有相同的地层深度,因此第一个千年的700年左右的历史是虚幻的岁月。” 换句话说,第一个千年只持续了大约300年。“根据地层学,所有早期的日期相比现在也必须缩短了700年。因此,最后一个世纪的晚期拉坦诺文化(公元前100年至公元前1年,欧洲铁器时代),移动到公元600年至700年左右。

由于230年代的大灾难与530年代或930年代的大灾难具有相同的地层深度,因此第一个千年的700年左右的历史是虚幻的岁月。” 换句话说,第一个千年只持续了大约300年。“根据地层学,所有早期的日期相比现在也必须缩短了700年。因此,最后一个世纪的晚期拉坦诺文化(公元前100年至公元前1年,欧洲铁器时代),移动到公元600年至700年左右。

All over the Mediterranean world “three blocks of time have left — in any individual site — just one block of strata covering some 230 years.” Wherever they are found, the strata for Imperial Antiquity and Late Antiquity lie just underneath the tenth century and therefore really belong to the Early Middle Age, that is, 700-930 AD. The distinction between Antiquity, Late Antiquity and Early Middle Age is a cultural representation that has no basis in reality. Heinsohn proposes contemporaneity of the three periods, because they “are all found at the same stratigraphic depth, and must, therefore, end simultaneously in the 230s CE (being also the 520s and 930s).” “Thus, the three parallel time-blocks now found in our history books in a chronological sequence must be brought back to their stratigraphical position.” In this way, “the early medi period (approx. 700-930s AD) becomes the epoch for which history can finally be written because it contains Imperial Antiquity and Late Antiquity, too.”

在整个地中海世界,“在任何一个单独的地点,只留下了三个时间地块,一个地层块覆盖了大约230年。”无论在哪里发现,帝国古代和晚期古代的地层就在10世纪的下面,因此其真正断代为中世纪早期,也就是公元700-930年。

古代、晚期和中世纪早期的区别是一种没有现实基础的文化表征。海因索恩认为这三个时期是同时代的,因为它们“都是在同一地层深度发现的,因此也必须同时结束于公元230年代(同时也是520年代-930年代)。”

“因此,我们现在在历史书中发现的按时间顺序排列的三个平行时间块必须回到它们的地层位置。” 通过这种方式,“中世纪早期”(大约公元700-930年)成为历史最终可以被书写的时代,期间也包含了(传统认为属于)帝国古代和晚期古代的时代。”

在整个地中海世界,“在任何一个单独的地点,只留下了三个时间地块,一个地层块覆盖了大约230年。”无论在哪里发现,帝国古代和晚期古代的地层就在10世纪的下面,因此其真正断代为中世纪早期,也就是公元700-930年。

古代、晚期和中世纪早期的区别是一种没有现实基础的文化表征。海因索恩认为这三个时期是同时代的,因为它们“都是在同一地层深度发现的,因此也必须同时结束于公元230年代(同时也是520年代-930年代)。”

“因此,我们现在在历史书中发现的按时间顺序排列的三个平行时间块必须回到它们的地层位置。” 通过这种方式,“中世纪早期”(大约公元700-930年)成为历史最终可以被书写的时代,期间也包含了(传统认为属于)帝国古代和晚期古代的时代。”

As a result of stretching 230 years into 930 years, history is now distributed unevenly, each time-block having most of its recorded events localized in one of three geographical zones: Roman South-West, Byzantine South-East, and Germanic-Slavic North. If we look at written sources, “we have [for the 1st-3rd century] a spotlight on Rome, but know little about the 1st-3rd century in Constantinople or Aachen. Then we have a spotlight on Ravenna and Constantinople, but know little about the 4th-7th century in Rome or Aachen. Finally, we have a spotlight on Aachen in the 8th-10th century, but hardly know any details from Rome or Constantinople. I turn on all the lights at the same time and, thus, can see connections that were previously considered dark or completely unrecognizable.”

由于从230年延伸到930年,历史现在分布不均匀,每个时间段的大部分记录事件都集中在三个地理区域之一:罗马西南部、拜占庭东南部和日耳曼-斯拉夫北部。如果我们看书面资料,“我们(在1 -3世纪)对罗马有关注,但对君士坦丁堡或亚琛的1 -3世纪知之甚少。然后我们关注拉文纳和君士坦丁堡,但对4 -7世纪的罗马和亚琛知之甚少。最后,我们关注的是8 -10世纪的亚琛,但几乎不知道罗马或君士坦丁堡的细节。我同时打开所有的灯,因此可以看到以前被认为是黑暗或完全无法识别的历史事件之前的关联。”

由于从230年延伸到930年,历史现在分布不均匀,每个时间段的大部分记录事件都集中在三个地理区域之一:罗马西南部、拜占庭东南部和日耳曼-斯拉夫北部。如果我们看书面资料,“我们(在1 -3世纪)对罗马有关注,但对君士坦丁堡或亚琛的1 -3世纪知之甚少。然后我们关注拉文纳和君士坦丁堡,但对4 -7世纪的罗马和亚琛知之甚少。最后,我们关注的是8 -10世纪的亚琛,但几乎不知道罗马或君士坦丁堡的细节。我同时打开所有的灯,因此可以看到以前被认为是黑暗或完全无法识别的历史事件之前的关联。”

Each period ends with a demographic, architectural, technical, and cultural collapse, caused by a cosmic catastrophe and accompanied by plague. Historians “have identified major mega-catastrophes shaking the earth in three regions of Europe (South-West [230s]; South-East [530s], and Slavic North [940s]) within the 1st millennium.” “The catastrophic ends of (1) Imperial Antiquity, (2) Late Antiquity, and (3) the Early Middles Ages sit in the same stratigraphic plane immediately before the High Middle Ages (beginning around 930s AD).” Therefore these three devastating collapses of civilization are one and the same, which Heinsohn refers to as “the Tenth Century Collapse.”

每个时期都以人口、建筑、技术和文化的崩溃结束,这是由大范围灾难和瘟疫引起的。历史学家“已经确定了在欧洲三个地区(西南[230年代];东南[530年代]和斯拉夫北部[940年代])在第一个千年内。”

“(1)帝国古代,(2)古代晚期,(3)中世纪早期的灾难性结束,位于中世纪中期(大约始于公元930年)之前的同一个地层平面上。因此,这三次毁灭性的文明崩溃是同一事件,海因索恩称之为“十世纪崩溃”。

每个时期都以人口、建筑、技术和文化的崩溃结束,这是由大范围灾难和瘟疫引起的。历史学家“已经确定了在欧洲三个地区(西南[230年代];东南[530年代]和斯拉夫北部[940年代])在第一个千年内。”

“(1)帝国古代,(2)古代晚期,(3)中世纪早期的灾难性结束,位于中世纪中期(大约始于公元930年)之前的同一个地层平面上。因此,这三次毁灭性的文明崩溃是同一事件,海因索恩称之为“十世纪崩溃”。

Heinsohn’s identification of three time-blocks that should be synchronized is not to be taken as an exact parallelism: “This assumption does not claim a pure 1:1 parallelism in which events reported for the year 100 AD could simply be supplemented with information for the year 800 AD.”[18] Stratigraphic identity only means that all real events that are dated to Imperial Antiquity or Late Antiquity happened in fact during the Early Middle Ages (from the stratigraphic viewpoint).

海因索恩对三个应该同步的时间段的识别并不能被视为完全的并行:“这个假设并没有声称一个纯1:1的并行性。在这种平行性中,公元100年的事件报告可以简单地补充公元800年的信息。”

地层学的同一性只意味着所有可以追溯到帝国古代或上古晚期的真实事件实际上都发生在中世纪早期(从地层学的角度来看)。

海因索恩对三个应该同步的时间段的识别并不能被视为完全的并行:“这个假设并没有声称一个纯1:1的并行性。在这种平行性中,公元100年的事件报告可以简单地补充公元800年的信息。”

地层学的同一性只意味着所有可以追溯到帝国古代或上古晚期的真实事件实际上都发生在中世纪早期(从地层学的角度来看)。

Moreover, all three time-blocks do not have the same length. That is because Late Antiquity (from the beginning of Diocletian’s reign in 284 to the death of Heraclius in 641) is some 120 years too long, according to Heinsohn. The Byzantine segment from the rise of Justinian (527) to the death of Heraclius (641) was in reality shorter and overlapped with the period of Anastasius (491-518). In other words, not only the first millennium as a whole, but Late Antiquity itself has to be shortened. Duplicates account for its phantom years. Thus the Persian emperor Khosrow I (531-579) fought by Justinian is identical to the Khosrow II (591-628) fought by his immediate successors — regardless of the fact that archeologists decided to ascribe the silver drachmas to Khosrow I and the gold dinars to Khosrow II.

此外,这三个时间段的长度也不尽相同。根据海因索恩的说法,这是因为古代晚期(从284年戴克里先统治开始到641年希拉克略去世)大约长了120年。从查士丁尼(527年)崛起到希拉克略(641年)去世的拜占庭时期实际上更短,与阿纳斯塔修斯(491-518年)时期重叠。

换句话说,不仅是第一个千年作为一个整体,就连古代晚期本身都必须缩短。重复说明了它年代的虚幻。因此,查士丁尼与波斯皇帝科斯罗一世(531-579)的战争,与其直接继任者与科斯罗二世(591-628)的战争是一回事——尽管考古学家决定将银币德拉克马归科斯罗一世所有,将金币第纳尔归科斯罗二世所有。

此外,这三个时间段的长度也不尽相同。根据海因索恩的说法,这是因为古代晚期(从284年戴克里先统治开始到641年希拉克略去世)大约长了120年。从查士丁尼(527年)崛起到希拉克略(641年)去世的拜占庭时期实际上更短,与阿纳斯塔修斯(491-518年)时期重叠。

换句话说,不仅是第一个千年作为一个整体,就连古代晚期本身都必须缩短。重复说明了它年代的虚幻。因此,查士丁尼与波斯皇帝科斯罗一世(531-579)的战争,与其直接继任者与科斯罗二世(591-628)的战争是一回事——尽管考古学家决定将银币德拉克马归科斯罗一世所有,将金币第纳尔归科斯罗二世所有。

Other duplicates within Late Antiquity include the Roman emperor Flavius Theodosius (379-395) being identical to the Gothic ruler of Ravenna and Italy Flavius Theodoric (471-526), who bears the same name, only with the additional suffix riks, meaning king. “At some point in the half millennium with manipulations of the original texts that can no longer be counted or reconstructed, two names of one person have become two persons with different names placed one behind the other.” The Gothic wars have also been duplicated: with the war fought by Odoacer and his son Thela in the 470, and the one fought by ToTila in the 540s, “we are not dealing with two different Italian wars, but with two different narratives about the same war, which were connected chronologically one after the other.”

在古代晚期,其他重复的人包括罗马皇帝弗拉维乌斯·狄奥多西(379-395),他与拉文纳和意大利的哥特式统治者弗拉维乌斯·狄奥多里克(471-526)是一个人,他们的名字相同,只是多了一个后缀riks,意思是国王。“在半个世纪的某个时刻,由于对原始文本的操纵,无法再计数或重建,一个人的两个名字变成了有两个名字的不同的人,并且一个放在另一个后面。”

哥特战争也被复制了——奥多亚克和他的儿子西拉在公元470年发动的战争,以及托蒂拉在公元540年发动的战争,“我们面对的不是两场不同的意大利战争,而是对同一场战争的两种不同的叙述,它们按时间顺序一个接一个地联系在一起。”

在古代晚期,其他重复的人包括罗马皇帝弗拉维乌斯·狄奥多西(379-395),他与拉文纳和意大利的哥特式统治者弗拉维乌斯·狄奥多里克(471-526)是一个人,他们的名字相同,只是多了一个后缀riks,意思是国王。“在半个世纪的某个时刻,由于对原始文本的操纵,无法再计数或重建,一个人的两个名字变成了有两个名字的不同的人,并且一个放在另一个后面。”

哥特战争也被复制了——奥多亚克和他的儿子西拉在公元470年发动的战争,以及托蒂拉在公元540年发动的战争,“我们面对的不是两场不同的意大利战争,而是对同一场战争的两种不同的叙述,它们按时间顺序一个接一个地联系在一起。”

图:作者同时描绘了230年的三个时间段

The strength or Heinsohn’s approach, as compared to Illig and Niemtiz’s, is that he doesn’t really dexe history: “If one removes the span of time that has been artificially created by mistakenly placing parallel periods in sequence, only emptiness is lost, not history. By reuniting texts and artifacts that have now been chopped up and scattered over seven centuries, meaningful historiography becomes possible for the first time.” In fact, “a much richer image of Roman history emerges. The numerous actors from Iceland (with Roman coins; Heinsohn 2013d) to Baghdad (whose 9th c. coins are found in the same stratum as 2nd c. Roman coins; Heinsohn 2013b) can eventually be drawn together to weave the rich and colourful fabric of that vast space with 2.500 cities, and 85.000 km of roads.”

与伊利格和尼姆蒂斯的方法相比,海因索恩方法的优势在于,他并没有真正删除历史:“如果一个人删除了通过错误地将平行时期按顺序排列而人为创造的时间范围,那么失去的只是虚幻,而不是历史。通过重新整合七个世纪以来被切碎和分散的文本和文物,第一次有意义的历史编纂成为可能。”

事实上,“一幅更为丰富的罗马历史图景浮现了出来。来自冰岛的众多“演员”(罗马硬币)到巴格达(其公元9世纪的硬币与公元2世纪的罗马硬币在同一地层中被发现)最终可以与2500座城市和85000公里的道路结合在一起,编织出丰富多彩的广阔空间。”

与伊利格和尼姆蒂斯的方法相比,海因索恩方法的优势在于,他并没有真正删除历史:“如果一个人删除了通过错误地将平行时期按顺序排列而人为创造的时间范围,那么失去的只是虚幻,而不是历史。通过重新整合七个世纪以来被切碎和分散的文本和文物,第一次有意义的历史编纂成为可能。”

事实上,“一幅更为丰富的罗马历史图景浮现了出来。来自冰岛的众多“演员”(罗马硬币)到巴格达(其公元9世纪的硬币与公元2世纪的罗马硬币在同一地层中被发现)最终可以与2500座城市和85000公里的道路结合在一起,编织出丰富多彩的广阔空间。”

Rome

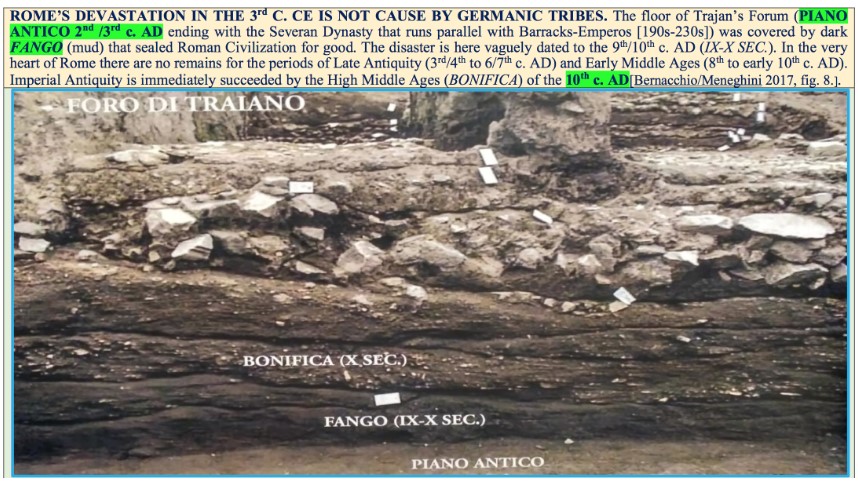

Applied to Rome, Heinsohn’s theory solves a conundrum that has always puzzled historians: the absence of any vestige datable from the late third century to the tenth century (mentioned in Part 1): “Rome of the first millennium CE builds residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc. only during Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd c.) but not in Late Antiquity (4th-6th c.) and in the Early Middle Ages (8th-10th c.). Since the ruins of the 3rd century lie directly under the primitive new buildings of the 10th century, Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from ca. 700 to 930 CE.”

罗马

应用于罗马,海因索恩的理论解决了一个一直困扰历史学家的难题:没有任何可以追溯到三世纪晚期到十世纪的遗迹(在第一部分中提到):“公元第一个千年的罗马只在帝国古代(公元1 -3世纪)建造了住宅区、厕所、水管、污水系统、街道、港口、面包店等,但在古代晚期(公元4 -6世纪)和中世纪早期(公元8 -10世纪)没有。由于3世纪的遗迹直接位于10世纪的原始新建筑之下,从地层学上讲,帝国古代属于公元700年至930年的时期。”

从公元3世纪到10世纪的7个世纪里,罗马帝国的中心没有任何新的建筑。公元3世纪的城市材料与公元10世纪初的城市材料在地层学上是一样的。”

在下面的插图中,图拉真广场(公元2 /3世纪的Piano Antico)的地板直接被罗马文明的大灾难所形成的黑泥(fango)层所覆盖。

Applied to Rome, Heinsohn’s theory solves a conundrum that has always puzzled historians: the absence of any vestige datable from the late third century to the tenth century (mentioned in Part 1): “Rome of the first millennium CE builds residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc. only during Imperial Antiquity (1st-3rd c.) but not in Late Antiquity (4th-6th c.) and in the Early Middle Ages (8th-10th c.). Since the ruins of the 3rd century lie directly under the primitive new buildings of the 10th century, Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from ca. 700 to 930 CE.”

罗马

应用于罗马,海因索恩的理论解决了一个一直困扰历史学家的难题:没有任何可以追溯到三世纪晚期到十世纪的遗迹(在第一部分中提到):“公元第一个千年的罗马只在帝国古代(公元1 -3世纪)建造了住宅区、厕所、水管、污水系统、街道、港口、面包店等,但在古代晚期(公元4 -6世纪)和中世纪早期(公元8 -10世纪)没有。由于3世纪的遗迹直接位于10世纪的原始新建筑之下,从地层学上讲,帝国古代属于公元700年至930年的时期。”

从公元3世纪到10世纪的7个世纪里,罗马帝国的中心没有任何新的建筑。公元3世纪的城市材料与公元10世纪初的城市材料在地层学上是一样的。”

在下面的插图中,图拉真广场(公元2 /3世纪的Piano Antico)的地板直接被罗马文明的大灾难所形成的黑泥(fango)层所覆盖。

In order to fill up their artificially stretched millennium, modern historians often have to do violence to their primary sources. As Fomenko already pointed out, the Getae and the Goths were considered the same people by Jordanes — himself a Goth — in his Getica written in the middle of the 6th century. Other historians before and after him, such as Claudian, Isidore of Seville and Procopius of Caesarea also used the name Getae to designate the Goths. But Theodor Mommsen has rejected the identification: “The Getae were Thracians, the Goths Germans, and apart from the coincidental similarity in their names they had nothing whatever in common.”

为了填满他们人为拉长的千年,现代历史学家经常不得不对他们的原始资料进行暴力处理。正如福门科已经指出的,在6世纪中期的《Getica》中,约旦人(他自己也是哥特人)认为盖塔(Getae)人和哥特(Goths)人是同一种人。

在他之前和之后的其他历史学家,如克劳狄、塞维利亚的伊西多尔和凯撒利亚的普罗科匹厄斯也用盖塔(Getae)这个名字来称呼哥特人。但是莫姆森否认了这一说法:

“盖塔人是色雷斯人,哥特人是日耳曼人,除了名字巧合相似之外,他们没有任何共同之处。”

Yet archeologists are puzzled by the fact that the Getae and the Goths inhabit the same area at 300 years distance, and there is no explanation for how the Getae disappeared before the Goth appeared, and for the lack of demography during the 300-year interval. Besides, there is evidence, contrary to what Mommsen claims, of great resemblance between their culture, including in clothing, as Gunnar Heinsohn points out: Goths in the 3rd/4th c. “made great efforts to dress, from head to toe, like their mysteriously missing predecessors” (the 1st/3rd-c. Getae), and continued “to manufacture 300 year older ceramics, rolling back technological evolution to pre-Christian La Tène earthenware.”

然而,考古学家对盖塔人和哥特人相隔300年居住在同一地区的事实感到困惑,而且没有解释盖塔人如何在哥特人出现之前消失,以及在300年的间隔中缺乏人口统计。

此外,有证据表明,与莫姆森的说法相反,他们的文化非常相似,包括在服装上,正如海因索恩指出的那样:

“哥特人生活在3-4世纪,他们花了很大的努力,从头到脚打扮得像他们神秘失踪的前辈盖塔人一样”(公元1 -3世纪),并继续“制造300年前的陶瓷,其技术进化可以回溯到基督教之前的拉坦诺文化的陶器。”

然而,考古学家对盖塔人和哥特人相隔300年居住在同一地区的事实感到困惑,而且没有解释盖塔人如何在哥特人出现之前消失,以及在300年的间隔中缺乏人口统计。

此外,有证据表明,与莫姆森的说法相反,他们的文化非常相似,包括在服装上,正如海因索恩指出的那样:

“哥特人生活在3-4世纪,他们花了很大的努力,从头到脚打扮得像他们神秘失踪的前辈盖塔人一样”(公元1 -3世纪),并继续“制造300年前的陶瓷,其技术进化可以回溯到基督教之前的拉坦诺文化的陶器。”

According to Heinsohn, “The identity of Getae and Goths can help to solve some of the most stubborn enigmas of Gothic history,” such as strong parallel between Rome’s Getic-Dacian wars in the first century AD and Rome’s Gothic wars some 300 years later. The Dacian leader Decebalus (meaning “The Powerful”) may be identical to the Goth Alaric (meaning “King of all”). By such processes, “different sources dealing with the same events have been split (and altered) in such a way that the same event is described twice, albeit from different angles, thereby creating a chronology that is twice as long as the actual course of history that can be substantiated by archaeology.”

根据海因索恩的说法,“盖塔人和哥特人的身份可以帮助解决哥特历史上一些最顽固的谜题”,比如公元1世纪罗马的盖塔-达契亚战争与大约300年后罗马的哥特战争之间的强烈相似性。

达契亚领袖德塞巴罗斯(意为“强大的”)可能与哥特人阿拉里克(意为“所有人的国王”)是一个人。通过这样的过程,“处理同一事件的不同来源被分拨缕析(和改变),以这样一种方式,同一事件被描述了两次,尽管是从不同的角度,从而创造了一个比考古学可以证实的实际历史进程长两倍的年表。”

根据海因索恩的说法,“盖塔人和哥特人的身份可以帮助解决哥特历史上一些最顽固的谜题”,比如公元1世纪罗马的盖塔-达契亚战争与大约300年后罗马的哥特战争之间的强烈相似性。

达契亚领袖德塞巴罗斯(意为“强大的”)可能与哥特人阿拉里克(意为“所有人的国王”)是一个人。通过这样的过程,“处理同一事件的不同来源被分拨缕析(和改变),以这样一种方式,同一事件被描述了两次,尽管是从不同的角度,从而创造了一个比考古学可以证实的实际历史进程长两倍的年表。”

图:盖塔囚犯和哥特战士,都穿着同样的衣服,包括弗里吉亚的帽子

Constantinople

“While no new residential areas with latrines, water systems and streets were built in Rome during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, they are missing in Constantinople during Imperial Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. […] Both cities have these basic components of urbanity in only one of the three epochs of the first millennium. Although in Rome they are dated to Imperial Antiquity, whilst in Constantinople they are dated to Late Antiquity, from the point of view of architecture and building technology they are nearly indistinguishable.” That is because, in reality, they “share the same stratigraphical horizon.”

君士坦丁堡

“虽然在古代晚期和中世纪早期,罗马没有建造带有厕所、供水系统和街道的新住宅区,但他们无视了在帝国古代和中世纪早期的君士坦丁堡。……这两个城市在第一个千年的三个时期中只有一个时期具有城市化的这些基本组成部分。虽然在罗马,它们可以追溯到帝国时期而在君士坦丁堡它们可以追溯到古代晚期,但从建筑和建筑技术的角度来看,它们几乎没有什么区别。这是因为,在现实中,它们“共享相同的地层面。”

“While no new residential areas with latrines, water systems and streets were built in Rome during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, they are missing in Constantinople during Imperial Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. […] Both cities have these basic components of urbanity in only one of the three epochs of the first millennium. Although in Rome they are dated to Imperial Antiquity, whilst in Constantinople they are dated to Late Antiquity, from the point of view of architecture and building technology they are nearly indistinguishable.” That is because, in reality, they “share the same stratigraphical horizon.”

君士坦丁堡

“虽然在古代晚期和中世纪早期,罗马没有建造带有厕所、供水系统和街道的新住宅区,但他们无视了在帝国古代和中世纪早期的君士坦丁堡。……这两个城市在第一个千年的三个时期中只有一个时期具有城市化的这些基本组成部分。虽然在罗马,它们可以追溯到帝国时期而在君士坦丁堡它们可以追溯到古代晚期,但从建筑和建筑技术的角度来看,它们几乎没有什么区别。这是因为,在现实中,它们“共享相同的地层面。”

There are, however, non-residential constructions in Byzantium dated from Imperial Antiquity. The most important is its first recorded aqueduct, built under Hadrian (117-138 AD). “This is considered a mystery because Byzantium’s actual founder, Constantine the Great (305-337 AD), did not expand the city until 200 years later.” In reality, “Hadrian’s aqueduct carries water to a flourishing city 100 years after Constantine, and not to a supposed wasteland centuries earlier. The mystery disappears. When Justinian renovates the great Basilica Cistern, which gathers water from Hadrian’s aqueduct, he does so not 400 years, but less than 100 years after it was built.”

然而,拜占庭的非住宅建筑可以追溯到帝国古代。最重要的是有记载的第一条渡槽,建于哈德良(公元117-138年)时期。“这被认为是一个谜,因为拜占庭的真正创始人君士坦丁大帝(公元305-337年)直到200年后才扩建这座城市。”

在现实中,“哈德良的水渠将水输送到君士坦丁之后100年的繁荣城市,而不是几个世纪前的一片荒原。”神秘消失了。当查士丁尼修复从哈德良的渡槽中收集水的大殿蓄水池时,不是400年后,而是建成后不到100年。”

然而,拜占庭的非住宅建筑可以追溯到帝国古代。最重要的是有记载的第一条渡槽,建于哈德良(公元117-138年)时期。“这被认为是一个谜,因为拜占庭的真正创始人君士坦丁大帝(公元305-337年)直到200年后才扩建这座城市。”

在现实中,“哈德良的水渠将水输送到君士坦丁之后100年的繁荣城市,而不是几个世纪前的一片荒原。”神秘消失了。当查士丁尼修复从哈德良的渡槽中收集水的大殿蓄水池时,不是400年后,而是建成后不到100年。”

The Early Middle Ages are known as Byzantium’s Dark Ages, beginning in 641 after the reign of Heraclius, and ending with the Macedonian Renaissance under Basil II (976-1022 AD). In the words of historian John O’Neill, “About forty years after the death of Justinian the Great, from the first quarter of the seventh century, [for] three centuries, cities were abandoned and urban life came to an end. There is no sign of revival until the middle of the tenth century.” For Heinsohn, this period, like most other “dark ages”, is a phantom age. The Justinian dynasty starting with Justin I (AD 518-527) is identical to the Macedonian dynasty, which we can count from Constantine VII (913-959), initiator of the Macedonian Renaissance. The 400-year period between Justinian (527-565 AD) and Basil II lasted in reality only 70 years, corresponding to the Tenth Century Collapse.

中世纪早期被称为拜占庭的黑暗时代,开始于赫拉克利乌斯统治后的641年,结束于巴兹尔二世统治下的马其顿文艺复兴时期(公元976-1022年)。用历史学家约翰·奥尼尔的话来说,“查士丁尼大帝死后大约四十年,也就是从七世纪上半叶开始的三个世纪里,城市被遗弃了,城市生活走到了尽头。直到十世纪中叶才出现复兴的迹象。对海因索恩来说,这一时期和其他大多数“黑暗时代”一样,是一个虚幻时代。

查士丁尼王朝始于犹斯丁一世(公元518-527年),与马其顿王朝相同,我们可以从君士坦丁七世(公元913-959年)算起,他是马其顿文艺复兴的发起者。查士丁尼(公元527-565年)和巴兹尔二世之间的400年,实际上只持续了70年,相当于10世纪大崩溃。

中世纪早期被称为拜占庭的黑暗时代,开始于赫拉克利乌斯统治后的641年,结束于巴兹尔二世统治下的马其顿文艺复兴时期(公元976-1022年)。用历史学家约翰·奥尼尔的话来说,“查士丁尼大帝死后大约四十年,也就是从七世纪上半叶开始的三个世纪里,城市被遗弃了,城市生活走到了尽头。直到十世纪中叶才出现复兴的迹象。对海因索恩来说,这一时期和其他大多数“黑暗时代”一样,是一个虚幻时代。

查士丁尼王朝始于犹斯丁一世(公元518-527年),与马其顿王朝相同,我们可以从君士坦丁七世(公元913-959年)算起,他是马其顿文艺复兴的发起者。查士丁尼(公元527-565年)和巴兹尔二世之间的400年,实际上只持续了70年,相当于10世纪大崩溃。

Besides archeology, there are also “anachronisms and puzzles in the development of the laws of Justinian (527-535 CE),” written in 2nd-c. Latin. “Not a single jurist from the 300 years between the Severan early 3rd century and Justinian’s 6th century textbook date is included in the Digestae. Moreover, no post-550s jurist put his hand to the Digestae.” So that “There are, from the Severans to the end of the Early Middle Ages, some 700 years without comments by Roman jurists.” In addition: “It is a mystery why Justinian’s Greek subjects had to wait 370 years [until the 900s CE], only to receive a version of the laws in Koine Greek of the 2nd c. out of use since 700 years.” It all “looks bizarre only as long as the stratigraphic simultaneity of Imperial Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and the Early Middle Ages is denied.” That the Severan and the Justinian dynasties are contemporaries explain that both fought a Persian emperor named Khosrow.

除了考古学,还有《学说汇纂》——写于公元2世纪的“查士丁尼(公元527-535年)法律发展中的时代错误和困惑”。写于拉丁语。“从3世纪早期的塞维兰到6世纪查士丁尼的教科书日期之间的300年间,没有一个法学家被包括在《学说汇纂》中。而且,没有一个550 年后的法学家把手放在《学说汇纂》上。”

因此,“从塞维兰王朝到中世纪早期,大约有700年没有罗马法学家的评论。”此外,“查士丁尼的希腊臣民为什么要等370年(直到公元900年),才得到公元2世纪的希腊共同语版本的法律,这是一个谜,从700年开始就没有使用过。”

这一切“只有在否认帝国古代、古代晚期和中世纪早期的地层同一性时,才会显得奇怪”。塞维兰王朝和查士丁尼王朝是同时代的,顺带这也解释了他们都与波斯皇帝科斯罗作战。

除了考古学,还有《学说汇纂》——写于公元2世纪的“查士丁尼(公元527-535年)法律发展中的时代错误和困惑”。写于拉丁语。“从3世纪早期的塞维兰到6世纪查士丁尼的教科书日期之间的300年间,没有一个法学家被包括在《学说汇纂》中。而且,没有一个550 年后的法学家把手放在《学说汇纂》上。”

因此,“从塞维兰王朝到中世纪早期,大约有700年没有罗马法学家的评论。”此外,“查士丁尼的希腊臣民为什么要等370年(直到公元900年),才得到公元2世纪的希腊共同语版本的法律,这是一个谜,从700年开始就没有使用过。”

这一切“只有在否认帝国古代、古代晚期和中世纪早期的地层同一性时,才会显得奇怪”。塞维兰王朝和查士丁尼王朝是同时代的,顺带这也解释了他们都与波斯皇帝科斯罗作战。

According to Heinsohn, the foundation of Imperial Rome and Imperial Constantinople are roughly contemporary. It is “a geographical sequence from west to east [that] was turned into a chronological sequence from earlier to later.” “Diocletian did not reside in ruins, but lived at the same time as Augustus. His capital was not Rome. He had residences in Antioch, Nicomedia, and Sirmium. From there he worked tirelessly for the protection of Augustus’ empire.” Heinsohn’s hypothesis of the contemporaneity of Diocletian in the East and Octavian Augustus in the West (ruling in concert) distinguishes him from Fomenko, who believes that Augustus is a fictitious duplicate of the Roman Emperor residing in Constantinople. Heinsohn also differs from Fomenko in the way he sees the relationship between the two Roman capitals: he accepts Rome’s precedence and assumes that Diocletian was a subordinate of Octavian Augustus. Fomenko, on the other hand, considers that Constantinople was the original center of the empire. This is consistent with Diocletian’s position as the superior of his Western counterpart Maximian. Diocletian was an Eastern Emperor from the beginning. He was born in today’s Croatia, where he built his palace (Split), and hardly ever set foot in Rome. Maximian, sent to rule in Rome, was himself from the Balkans.

根据海因索恩的说法,罗马帝国和君士坦丁堡帝国的建立大致是在同一时期。它从“一个原本从西到东的地理序列,变成了一个从早到晚的时间序列。

“戴克里先并没有居住在废墟中,而是和奥古斯都生活在同一时代。他的首都不是罗马。他在安提阿、尼科米底亚和锡尔米乌姆都有住处。在那里,他不知疲倦地为保护奥古斯都的帝国而工作。”

海因索恩的假设是东方的戴克里先和西方的屋大维奥古斯都在同一时期,这使他与福门科区别开来,后者认为奥古斯都是居住在君士坦丁堡的罗马皇帝的虚构复制品。海因索恩对两个罗马首都之间关系的看法也与福门科不同,他接受罗马的优先地位,并认为戴克里先是屋大维的下属。而福门科则认为君士坦丁堡是帝国最初的中心。

这与戴克里先的地位是一致的,他是西方同行马克西米安的上级。戴克里先从一开始就是东方皇帝。他出生在今天的克罗地亚,并在那里建造了自己的宫殿(斯普利特),几乎从未踏足罗马。被派到罗马统治的马克西米安本人则来自巴尔干半岛。

(未完待续)

根据海因索恩的说法,罗马帝国和君士坦丁堡帝国的建立大致是在同一时期。它从“一个原本从西到东的地理序列,变成了一个从早到晚的时间序列。

“戴克里先并没有居住在废墟中,而是和奥古斯都生活在同一时代。他的首都不是罗马。他在安提阿、尼科米底亚和锡尔米乌姆都有住处。在那里,他不知疲倦地为保护奥古斯都的帝国而工作。”

海因索恩的假设是东方的戴克里先和西方的屋大维奥古斯都在同一时期,这使他与福门科区别开来,后者认为奥古斯都是居住在君士坦丁堡的罗马皇帝的虚构复制品。海因索恩对两个罗马首都之间关系的看法也与福门科不同,他接受罗马的优先地位,并认为戴克里先是屋大维的下属。而福门科则认为君士坦丁堡是帝国最初的中心。

这与戴克里先的地位是一致的,他是西方同行马克西米安的上级。戴克里先从一开始就是东方皇帝。他出生在今天的克罗地亚,并在那里建造了自己的宫殿(斯普利特),几乎从未踏足罗马。被派到罗马统治的马克西米安本人则来自巴尔干半岛。

(未完待续)

评论翻译

(见末篇)

很赞 ( 3 )

收藏