古罗马历史到底有多假?(一) 那些伪造的手稿

古罗马历史到底有多假?(一) 那些伪造的手稿

How Fake Is Roman Antiquity?

译文简介

本文是挑战地中海世界从罗马帝国到十字军东征的传统历史框架的三篇系列文章中的第一篇。

正文翻译

This is the first of a series of three articles challenging the conventional historical frxwork of the Mediterranean world from the Roman Empire to the Crusades. It is a collective contribution to an old debate that has gained new momentum in recent decades in the fringe of the academic world, mostly in Germany, Russia, and France. Some working hypotheses will be made along the way, and the final article will suggest a global solution in the form of a paradigm shift based on hard archeological evidence.

本文是挑战地中海世界从罗马帝国到十字军东征的传统历史框架的三篇系列文章中的第一篇。这是对一场古老辩论的集体贡献,近几十年来,这场辩论在学术界的边缘(主要是在德国、俄罗斯和法国)获得了新的动力。在此过程中,我们将提出一些可行的假设,最后一篇文章将基于确凿的考古证据,以范式转变的形式提出一个全球性的解决方案。

本文是挑战地中海世界从罗马帝国到十字军东征的传统历史框架的三篇系列文章中的第一篇。这是对一场古老辩论的集体贡献,近几十年来,这场辩论在学术界的边缘(主要是在德国、俄罗斯和法国)获得了新的动力。在此过程中,我们将提出一些可行的假设,最后一篇文章将基于确凿的考古证据,以范式转变的形式提出一个全球性的解决方案。

Tacitus and Bracciolini

One of our most detailed historical sources on imperial Rome is Cornelius Tacitus (56-120 CE), whose major works, the Annals and the Histories, span the history of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus in 14 AD, to the death of Domitian in 96.

Here is how the French scholar Polydor Hochart introduced in 1890 the result of his investigation on “the authenticity of the Annals and the Histories of Tacitus,” building up on the work of John Wilson Ross published twelve years earlier, Tacitus and Bracciolini: The Annals forged in the XVth century (1878):

塔西佗和布拉乔里尼

我们对罗马帝国最详细的历史资料之一是科尼利厄斯·塔西佗(公元56-120年),他的主要著作《编年史》(the Annals)和《历史》(the Histories)涵盖了罗马帝国的历史,从公元14年奥古斯都去世到96年多米提安去世。

法国学者Polydor Hochart在1890年介绍了他对“塔西佗编年史和历史的真实性”的调查结果,该调查是在约翰·威尔逊·罗斯12年前出版的《塔西佗和布拉乔利尼:15世纪伪造的编年史》(1878年)的基础上进行的:

One of our most detailed historical sources on imperial Rome is Cornelius Tacitus (56-120 CE), whose major works, the Annals and the Histories, span the history of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus in 14 AD, to the death of Domitian in 96.

Here is how the French scholar Polydor Hochart introduced in 1890 the result of his investigation on “the authenticity of the Annals and the Histories of Tacitus,” building up on the work of John Wilson Ross published twelve years earlier, Tacitus and Bracciolini: The Annals forged in the XVth century (1878):

塔西佗和布拉乔里尼

我们对罗马帝国最详细的历史资料之一是科尼利厄斯·塔西佗(公元56-120年),他的主要著作《编年史》(the Annals)和《历史》(the Histories)涵盖了罗马帝国的历史,从公元14年奥古斯都去世到96年多米提安去世。

法国学者Polydor Hochart在1890年介绍了他对“塔西佗编年史和历史的真实性”的调查结果,该调查是在约翰·威尔逊·罗斯12年前出版的《塔西佗和布拉乔利尼:15世纪伪造的编年史》(1878年)的基础上进行的:

“At the beginning of the fifteenth century scholars had at their disposal no part of the works of Tacitus; they were supposed to be lost. It was around 1429 that Poggio Bracciolini and Niccoli of Florence brought to light a manuscxt that contained the last six books of the Annals and the first five books of the Histories. It is this archetypal manuscxt that served to make the copies that were in circulation until the use of printing. Now, when one wants to know where and how it came into their possession, one is surprised to find that they have given unacceptable explanations on this subject, that they either did not want or could not say the truth. About eighty years later, Pope Leo X was given a volume containing the first five books of the Annals. Its origin is also surrounded by darkness. / Why these mysteries? What confidence do those who exhibited these documents deserve? What guarantees do we have of their authenticity? / In considering these questions we shall first see that Poggio and Niccoli were not distinguished by honesty and loyalty, and that the search for ancient manuscxts was for them an industry, a means of acquiring money. / We will also notice that Poggio was one of the most learned men of his time, that he was also a clever calligrapher, and that he even had in his pay scribes trained by him to write on parchment in a remarkable way in Lombard and Carolin characters. Volumes coming out of his hands could thus imitate perfectly the ancient manuscxts, as he says himself. / We will also be able to see with what elements the Annals and the Histories were composed. Finally, in seeking who may have been the author of this literary fraud, we shall be led to think that, in all probability, the pseudo-Tacitus is none other than Poggio Bracciolini himself.”

"在15世纪初,学者们没有塔西佗的任何著作;它们应该是遗失了。大约在1429年,佛罗伦萨的波乔·布拉乔利尼和尼科利发现了一份手稿,其中包括《编年史》的后六卷和《历史》的前五卷。在印刷术使用之前,正是这种原型手稿制作了流通中的副本。现在,当你想知道他们是在哪里以及如何得到它的时候,你会惊讶地发现,他们对这个问题的解释是不可接受的,他们要么不想说,要么不能说真话。大约80年后,教皇利奥十世得到了一本包含《编年史》前五卷的书。它的发现也被黑暗所包围。

为什么会有这些谜团?展示这些古籍的人应该得到多大程度的信任?我们对它们的真实性有什么保证?在考虑这些问题时,我们首先会看到,波乔和尼科利并不以诚实和忠诚著称,对他们来说,寻找古代手稿是一种行业,一种赚钱的手段。

我们还会注意到,波乔是他那个时代最有学问的人之一,他也是一个聪明的书法家,他甚至付费训练了抄写员,用伦巴第和卡洛林的文字在羊皮纸上以一种非凡的方式书写。就像他自己说的那样,从他手中出来的书可以完美地模仿古代手稿。/我们也将能够看到《编年史》和《历史》是用什么元素组成的。最后,在寻找谁可能是这个文学骗局的作者时,我们将被引导认为,在所有的可能性中,伪塔西佗不是。”

"在15世纪初,学者们没有塔西佗的任何著作;它们应该是遗失了。大约在1429年,佛罗伦萨的波乔·布拉乔利尼和尼科利发现了一份手稿,其中包括《编年史》的后六卷和《历史》的前五卷。在印刷术使用之前,正是这种原型手稿制作了流通中的副本。现在,当你想知道他们是在哪里以及如何得到它的时候,你会惊讶地发现,他们对这个问题的解释是不可接受的,他们要么不想说,要么不能说真话。大约80年后,教皇利奥十世得到了一本包含《编年史》前五卷的书。它的发现也被黑暗所包围。

为什么会有这些谜团?展示这些古籍的人应该得到多大程度的信任?我们对它们的真实性有什么保证?在考虑这些问题时,我们首先会看到,波乔和尼科利并不以诚实和忠诚著称,对他们来说,寻找古代手稿是一种行业,一种赚钱的手段。

我们还会注意到,波乔是他那个时代最有学问的人之一,他也是一个聪明的书法家,他甚至付费训练了抄写员,用伦巴第和卡洛林的文字在羊皮纸上以一种非凡的方式书写。就像他自己说的那样,从他手中出来的书可以完美地模仿古代手稿。/我们也将能够看到《编年史》和《历史》是用什么元素组成的。最后,在寻找谁可能是这个文学骗局的作者时,我们将被引导认为,在所有的可能性中,伪塔西佗不是。”

Hochart’s demonstration proceeds in two stages. First, he traces the origin of the manuscxt discovered by Poggio and Niccoli, using Poggio’s correspondence as evidence of deception. Then Hochart deals with the emergence of the second manuscxt, two years after Pope Leo X (a Medici) had promised great reward in gold to anyone who could provide him with unknown manuscxts of the ancient Greeks or Romans. Leo rewarded his unknown provider with 500 golden crowns, a fortune at that time, and immediately ordered the printing of the precious manuscxt. Hochart concludes that the manuscxt must have been supplied indirectly to Leo X by Jean-François Bracciolini, the son and sole inheritor of Poggio’s private library and papers, who happened to be secretary of Leo X at that time, and who used an anonymous intermediary in order to elude suspicion.

Hochart的论证分为两个阶段。首先,他追溯了波乔和尼科利发现的手稿的来源,用波乔的通信作为欺骗的证据。然后,Hochart处理了第二份手稿的出现,两年前,教皇利奥十世(美第奇家族)曾承诺,任何人只要能向他提供古希腊或罗马的未知手稿,就会得到丰厚的黄金奖励。利奥给了这位不知名的提供者500个金克朗,这在当时是一笔财富,并立即下令印刷这珍贵的手稿。Hochart的结论是,手稿一定是由让-弗朗索瓦·布拉乔利尼间接提供给利奥十世的,让-弗朗索瓦·布拉乔利尼是波乔私人图书馆和文件的唯一继承人,他当时恰好是利奥十世的秘书,为了避免怀疑,他使用了一个匿名的中间人。

Hochart的论证分为两个阶段。首先,他追溯了波乔和尼科利发现的手稿的来源,用波乔的通信作为欺骗的证据。然后,Hochart处理了第二份手稿的出现,两年前,教皇利奥十世(美第奇家族)曾承诺,任何人只要能向他提供古希腊或罗马的未知手稿,就会得到丰厚的黄金奖励。利奥给了这位不知名的提供者500个金克朗,这在当时是一笔财富,并立即下令印刷这珍贵的手稿。Hochart的结论是,手稿一定是由让-弗朗索瓦·布拉乔利尼间接提供给利奥十世的,让-弗朗索瓦·布拉乔利尼是波乔私人图书馆和文件的唯一继承人,他当时恰好是利奥十世的秘书,为了避免怀疑,他使用了一个匿名的中间人。

Both manuscxts are now preserved in Florence, so their age can be scientifically established, can’t it? That is questionable, but the truth, anyway, is that their age is simply assumed. For other works of Tacitus, such as Germania and De Agricola, we don’t even have any medi manuscxts. David Schaps tells us that Germania was ignored throughout the Middle Ages but survived in a single manuscxt that was found in Hersfeld Abbey in 1425, was brought to Italy and examined by Enea Silvio Piccolomini, later Pope Pius II, as well as by Bracciolini, then vanished from sight.

Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) is credited for “rediscovering and recovering a great number of classical Latin manuscxts, mostly decaying and forgotten in German, Swiss, and French monastic libraries” (Wikipedia). Hochart believes that Tacitus’ books are not his only forgeries. Under suspicion come other works by Cicero, Lucretius, Vitruvius, and Quintilian, to name just a few. For instance, Lucretius’ only known work, De rerum natura “virtually disappeared during the Middle Ages, but was rediscovered in 1417 in a monastery in Germany by Poggio Bracciolini” (Wikipedia).

两份手稿现在都保存在佛罗伦萨,所以它们的年代可以科学地确定,不是吗?这是值得怀疑的,但事实是,无论如何,它们的年代只是假设的。塔西佗的其他作品,比如《日耳曼尼亚》和《论农业》,我们甚至没有任何中世纪的手稿。大卫·夏普斯告诉我们,《日耳曼尼亚》在整个中世纪都被忽视了,但1425年在赫斯菲尔德修道院发现的一份手稿保存了下来,被带到意大利,由后来的教皇庇护二世和布拉奇奥利尼检查,然后从人们的视线中消失了。

Poggio Bracciolini(1380-1459)被认为“重新发现并恢复了大量古典拉丁语手稿,这些手稿大多已经腐烂并被遗忘在德国、瑞士和法国的修道院图书馆中”(维基百科)。Hochart认为塔西佗的书并不是他唯一的伪造作品。西塞罗、卢克莱修、维特鲁威和昆提连等人的其他作品也受到怀疑。例如,卢克莱修唯一为人所知的作品《论自然》“在中世纪几乎消失了,但1417年在德国的一座修道院被波乔·布拉乔利尼重新发现”(维基百科)。

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) is credited for “rediscovering and recovering a great number of classical Latin manuscxts, mostly decaying and forgotten in German, Swiss, and French monastic libraries” (Wikipedia). Hochart believes that Tacitus’ books are not his only forgeries. Under suspicion come other works by Cicero, Lucretius, Vitruvius, and Quintilian, to name just a few. For instance, Lucretius’ only known work, De rerum natura “virtually disappeared during the Middle Ages, but was rediscovered in 1417 in a monastery in Germany by Poggio Bracciolini” (Wikipedia).

两份手稿现在都保存在佛罗伦萨,所以它们的年代可以科学地确定,不是吗?这是值得怀疑的,但事实是,无论如何,它们的年代只是假设的。塔西佗的其他作品,比如《日耳曼尼亚》和《论农业》,我们甚至没有任何中世纪的手稿。大卫·夏普斯告诉我们,《日耳曼尼亚》在整个中世纪都被忽视了,但1425年在赫斯菲尔德修道院发现的一份手稿保存了下来,被带到意大利,由后来的教皇庇护二世和布拉奇奥利尼检查,然后从人们的视线中消失了。

Poggio Bracciolini(1380-1459)被认为“重新发现并恢复了大量古典拉丁语手稿,这些手稿大多已经腐烂并被遗忘在德国、瑞士和法国的修道院图书馆中”(维基百科)。Hochart认为塔西佗的书并不是他唯一的伪造作品。西塞罗、卢克莱修、维特鲁威和昆提连等人的其他作品也受到怀疑。例如,卢克莱修唯一为人所知的作品《论自然》“在中世纪几乎消失了,但1417年在德国的一座修道院被波乔·布拉乔利尼重新发现”(维基百科)。

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

So was Quintilian’s only extant work, a twelve-volume textbook on rhetoric entitled Institutio Oratoria, whose discovery Poggio recounts in a letter:

“There amid a tremendous quantity of books which it would take too long to describe, we found Quintilian still safe and sound, though filthy with mould and dust. For these books were not in the library, as befitted their worth, but in a sort of foul and gloomy dungeon at the bottom of one of the towers, where not even men convicted of a capital offence would have been stuck away.”

昆提连唯一现存的著作也是如此,一本十二卷的修辞学教科书,名为《演讲机构》(Institutio Oratoria),波乔在一封信中叙述了他的发现:

“在一大堆书中,我们发现昆提连还安然无恙,只是满是霉菌和灰尘。因为这些书并不是放在图书室里(这与它们的价值相称),而是放在一座塔楼底部的一间阴暗肮脏的地牢里,即使是被判了死罪的人也不会被关在那里。”

“There amid a tremendous quantity of books which it would take too long to describe, we found Quintilian still safe and sound, though filthy with mould and dust. For these books were not in the library, as befitted their worth, but in a sort of foul and gloomy dungeon at the bottom of one of the towers, where not even men convicted of a capital offence would have been stuck away.”

昆提连唯一现存的著作也是如此,一本十二卷的修辞学教科书,名为《演讲机构》(Institutio Oratoria),波乔在一封信中叙述了他的发现:

“在一大堆书中,我们发现昆提连还安然无恙,只是满是霉菌和灰尘。因为这些书并不是放在图书室里(这与它们的价值相称),而是放在一座塔楼底部的一间阴暗肮脏的地牢里,即使是被判了死罪的人也不会被关在那里。”

Provided Hochart is right, was Poggio the exception that confirms the rule of honesty among the humanists to whom humankind is indebted for “rediscovering” the great classics? Hardly, as we shall see. Even the great Erasmus (1465-1536) succumbed to the temptation of forging a treatise under the name of saint Cyprian (De duplici martyrio ad Fortunatum), which he pretended to have found by chance in an ancient library. Erasmus used this stratagem to voice his criticism of the Catholic confusion between virtue and suffering. In this case, heterodoxy gave the forger away. But how many forgeries went undetected for lack of originality? Giles Constable writes in “Forgery and Plagiarism in the Middle Ages”: “The secret of successful forgers and plagiarists is to attune the deceit so closely to the desires and standards of their age that it is not detected, or even suspected, at the time of creation.” In other words: “Forgeries and plagiarisms … follow rather than create fashion and can without paradox be considered among the most authentic products of their time.”

如果Hochart是对的,那么波乔是不是一个例外,证实了人类对“重新发现”伟大经典而感激的人文主义者的诚实原则呢?很难,我们将会见证的。即使是伟大的伊拉斯谟(1465-1536)也禁不住诱惑,伪造了一篇以圣塞普里安(De duplici martyrio ad Fortunatum)为名的论文,他假装是在一个古老的图书馆里偶然发现的。

伊拉斯谟用这个策略来批评天主教对美德和苦难的混淆。在这种情况下,异端暴露了伪造者。但有多少赝品因为缺乏原创性而未被发现呢?贾尔斯·康斯特布尔(Giles Constable)在《中世纪的伪造与抄袭》中写道:“造假者和剽窃者成功的秘诀在于,他们的骗局与他们那个时代的欲望和标准非常接近,以至于在创作时不会被发现,甚至不会被怀疑。”换句话说:“伪造和抄袭……不是创造时尚,而是追随时尚,可以毫无矛盾地加以考虑。

如果Hochart是对的,那么波乔是不是一个例外,证实了人类对“重新发现”伟大经典而感激的人文主义者的诚实原则呢?很难,我们将会见证的。即使是伟大的伊拉斯谟(1465-1536)也禁不住诱惑,伪造了一篇以圣塞普里安(De duplici martyrio ad Fortunatum)为名的论文,他假装是在一个古老的图书馆里偶然发现的。

伊拉斯谟用这个策略来批评天主教对美德和苦难的混淆。在这种情况下,异端暴露了伪造者。但有多少赝品因为缺乏原创性而未被发现呢?贾尔斯·康斯特布尔(Giles Constable)在《中世纪的伪造与抄袭》中写道:“造假者和剽窃者成功的秘诀在于,他们的骗局与他们那个时代的欲望和标准非常接近,以至于在创作时不会被发现,甚至不会被怀疑。”换句话说:“伪造和抄袭……不是创造时尚,而是追随时尚,可以毫无矛盾地加以考虑。

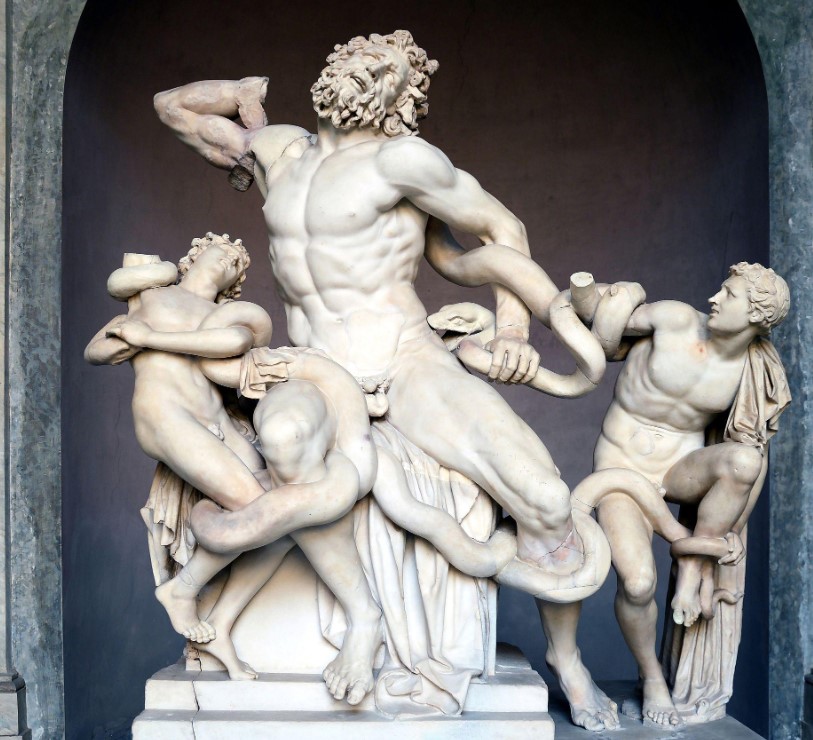

We are here focusing on literary forgeries, but there were other kinds. Michelangelo himself launched his own career by faking antique statues, including one known as the Sleeping Cupid (now lost), while under the employment of the Medici family in Florence. He used acidic earth to make the statue look antique. It was sold through a dealer to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio, who eventually found out the hoax and demanded his money back, but didn’t press any charges against the artist. Apart from this recognized forgery, Lynn Catterson has made a strong case that the sculptural group of “Laocoon and his Sons,” dated from around 40 BC and supposedly discovered in 1506 in a vineyard in Rome and immediately acquired by Pope Julius II, is another of Michelangelo’s forgery (read here)

我们在这里关注的是文学赝品,但还有其他种类。米开朗基罗在佛罗伦萨美第奇家族的雇佣下,通过伪造古董雕像开始了自己的职业生涯,其中包括一尊名为“沉睡的丘比特”(现已丢失)的雕像。他用酸土使雕像看起来古色古香。这幅画通过经销商卖给了圣乔治的里奥枢机主教,他最终发现了骗局,要求退还他的钱,但没有对这位艺术家提出任何指控。除了这幅公认的赝品外,林恩·卡特森还提出了一个强有力的证据,即《拉奥孔和他的儿子们》的雕塑群,大约创作于公元前40年,据说是1506年在罗马的一个葡萄园里发现的,并立即被教皇朱利叶斯二世收购,是米开朗基罗的另一尊赝品。

我们在这里关注的是文学赝品,但还有其他种类。米开朗基罗在佛罗伦萨美第奇家族的雇佣下,通过伪造古董雕像开始了自己的职业生涯,其中包括一尊名为“沉睡的丘比特”(现已丢失)的雕像。他用酸土使雕像看起来古色古香。这幅画通过经销商卖给了圣乔治的里奥枢机主教,他最终发现了骗局,要求退还他的钱,但没有对这位艺术家提出任何指控。除了这幅公认的赝品外,林恩·卡特森还提出了一个强有力的证据,即《拉奥孔和他的儿子们》的雕塑群,大约创作于公元前40年,据说是1506年在罗马的一个葡萄园里发现的,并立即被教皇朱利叶斯二世收购,是米开朗基罗的另一尊赝品。

When one comes to think about it seriously, one can find several reasons to doubt that such masterworks were possible any time before the Renaissance, one of them having to do with the progress in human anatomy. Many other antique works raise similar questions. For instance, a comparison between Marcus Aurelius’ bronze equestrian statue (formely thought to be Constantine’s), with, say, Louis XIV’s, makes you wonder: how come nothing remotely approaching this level of achievement can be found between the fifth and the fifteenth century? Can we even be sure that Marcus Aurelius is a historical figure? “The major sources depicting the life and rule of Marcus are patchy and frequently unreliable” (Wikipedia), the most important one being the highly dubious Historia Augusta (more later).

当我们认真思考这个问题时,我们可以找到几个理由来怀疑文艺复兴之前的任何时候都可能有这样的杰作,其中一个与人体解剖学的进步有关。许多其他古董作品也提出了类似的问题。例如,马可·奥勒留的青铜骑马雕像(以前被认为是君士坦丁的)与路易十四的雕像之间的比较,让你想知道:

为什么在五世纪到十五世纪之间,没有发现任何接近这一水平的成就?甚至,我们可以肯定马可·奥勒留是一个历史人物吗?“描述马库斯生活和统治的主要资料来源是不完整的,而且经常是不可靠的”(维基百科),最重要的是《奥古斯塔历史》是高度可疑的 (稍后)。

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处

The lucrative market of literary forgeries

“Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe, 1450-1800” was the subject of a 2012 conference, whose proceedings were published in 2018 by the John Hopkins University Press (who also published a 440-page catalog, Bibliotheca Fictiva: A Collection of Books & Manuscxts Relating to Literary Forgery, 400 BC-AD 2000). One forger discussed in that book is Annius of Viterbo (1432-1502), who produced a collection of eleven texts, attributed to a Chaldean, an Egyptian, a Persian, and several ancient Greeks and Romans, purporting to show that his native town of Viterbo had been an important center of culture during the Etruscan period. Annius attributed his texts to recognizable ancient authors whose genuine works had conveniently perished, and he went on producing voluminous commentaries on his own forgeries.

文学赝品利润丰厚的市场

“近代早期欧洲的文学伪造,1450-1800”,是2012年会议的主题,会议记录于2018年由约翰霍普金斯大学出版社出版(该出版社还出版了440页的目录,《Bibliotheca Fictiva:与文学伪造有关的书籍和手稿合集,公元前400年至公元2000年》)。

书中提到的一个伪造者是维泰博的阿尼乌斯(annus of Viterbo, 1432-1502),他制作了十一篇文献的合集,被认为是迦勒底人、埃及人、波斯人以及几个古希腊人和罗马人的作品,声称他的家乡维泰博在伊特鲁里亚时期是一个重要的文化中心。阿尼乌斯把他的作品归功于那些真迹已不了了之的古代作者,他持续为自己的赝品撰写大量评论。

This case illustrates the combination of political and mercantile motives in many literary forgeries. History-writing is a political act, and in the fifteenth century, it played a crucial role in the competition for prestige between Italian cities. Tacitus’ history of Rome was brought forward by Bracciolini thirty years after a Florentine chancellor by the name of Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444) wrote his History of the Florentine people (Historiae Florentini populi) in 12 volumes (by plagiarizing Byzantine chronicles). Political value translated into economic value, and the market for ancient works reached astronomical prices: it is said that with the sale of just a copy of a manuscxt of Titus Livy, Bracciolini bought himself a villa in Florence. During the Renaissance, “the acquisition of classical artifacts had simply become the new fad, the new way of displaying power and status. Instead of collecting the bones and body parts of saints, towns and wealthy rulers now collected fragments of the ancient world. And just as with the relic trade, demand far outstripped supply” (from the website of San Diego’s “Museum of Hoaxes”).

这个案例说明了许多文学赝品中政治和商业动机的结合。撰写历史是一种政治行为,在15世纪,它在意大利城市之间的声望竞争中发挥了至关重要的作用。塔西佗的罗马史是在佛罗伦萨总理莱昂纳多·布鲁尼(1369-1444)写了12卷的《佛罗伦萨人的历史》(Historiae Florentini populi)(抄袭拜占庭编年史)三十年后由布拉乔利尼提出的。

政治价值转化为经济价值,古代作品的市场价格达到了天文数字——据说,仅凭提图斯·李维(Titus Livy)的一份手稿,布拉乔利尼就在佛罗伦萨为自己买了一栋别墅。在文艺复兴时期,“获得古典文物已经成为一种新的时尚,一种展示权力和地位的新方式。城镇和富有的统治者不再收集圣人的骨头和身体部位,而是收集古代世界的碎片。就像文物交易一样,需求远远超过了供应”(来自圣地亚哥“恶作剧博物馆”的网站)。

这个案例说明了许多文学赝品中政治和商业动机的结合。撰写历史是一种政治行为,在15世纪,它在意大利城市之间的声望竞争中发挥了至关重要的作用。塔西佗的罗马史是在佛罗伦萨总理莱昂纳多·布鲁尼(1369-1444)写了12卷的《佛罗伦萨人的历史》(Historiae Florentini populi)(抄袭拜占庭编年史)三十年后由布拉乔利尼提出的。

政治价值转化为经济价值,古代作品的市场价格达到了天文数字——据说,仅凭提图斯·李维(Titus Livy)的一份手稿,布拉乔利尼就在佛罗伦萨为自己买了一栋别墅。在文艺复兴时期,“获得古典文物已经成为一种新的时尚,一种展示权力和地位的新方式。城镇和富有的统治者不再收集圣人的骨头和身体部位,而是收集古代世界的碎片。就像文物交易一样,需求远远超过了供应”(来自圣地亚哥“恶作剧博物馆”的网站)。

In the mainstream of classical studies, ancient texts are assumed to be authentic if they are not proven forged. Cicero’s De Consolatione is now universally considered the work of Carolus Sigonius (1520-1584), an Italian humanist born in Modena, only because we have a letter by Sigonius himself admitting the forgery. But short of such a confession, or of some blatant anachronism, historians and classical scholars will simply ignore the possibility of fraud. They would never, for example, suspect Francesco Petrarca, known as Petrarch (1304-1374), of faking his discovery of Cicero’s letters, even though he went on publishing his own letters in perfect Ciceronian style. Jerry Brotton is not being ironic when he writes in The Renaissance Bazaar: “Cicero was crucial to Petrarch and the subsequent development of humanism because he offered a new way of thinking about how the cultured individual united the philosophical and contemplative side of life with its more active and public dimension. […] This was the blueprint for Petrarch’s humanism.”

在古典研究的主流中,如果没有被证明是伪造的,古代文献就被认为是真实的。西塞罗的《安慰论》现在被普遍认为是卡洛勒斯·西格尼乌斯(1520-1584)的作品,西格尼乌斯是一位出生在摩德纳的意大利人文主义者,只因我们有西格尼乌斯本人的一封信承认这是伪造的。但是,如果没有这样的坦白,或者没有一些明显的时代错误,历史学家和古典学者就会简单地忽略欺诈的可能性。

例如,他们绝不会怀疑弗朗西斯科·佩特拉卡(又名彼特拉克(1304-1374))伪造了西塞罗信件的发现,尽管他继续以完美的西塞罗风格出版自己的信件。杰里·布洛顿在《文艺复兴时期的集市》中写道:“西塞罗对彼特拉克和随后的人文主义发展至关重要,因为他提供了一种新的思考方式,让人们了解有文化的个人如何将生活的哲学和沉思方面与更积极和公共的方面结合起来。”这是彼特拉克人文主义的蓝图。”

在古典研究的主流中,如果没有被证明是伪造的,古代文献就被认为是真实的。西塞罗的《安慰论》现在被普遍认为是卡洛勒斯·西格尼乌斯(1520-1584)的作品,西格尼乌斯是一位出生在摩德纳的意大利人文主义者,只因我们有西格尼乌斯本人的一封信承认这是伪造的。但是,如果没有这样的坦白,或者没有一些明显的时代错误,历史学家和古典学者就会简单地忽略欺诈的可能性。

例如,他们绝不会怀疑弗朗西斯科·佩特拉卡(又名彼特拉克(1304-1374))伪造了西塞罗信件的发现,尽管他继续以完美的西塞罗风格出版自己的信件。杰里·布洛顿在《文艺复兴时期的集市》中写道:“西塞罗对彼特拉克和随后的人文主义发展至关重要,因为他提供了一种新的思考方式,让人们了解有文化的个人如何将生活的哲学和沉思方面与更积极和公共的方面结合起来。”这是彼特拉克人文主义的蓝图。”

The medi manuscxts found by Petrarch are long lost, so what evidence do we have of their authenticity, besides Petrarch’s reputation? Imagine if historians seriously questioned the authenticity of some of our most cherished classical treasures. How many of them would pass the test? If Hochart is right and Tacitus is removed from the list of reliable sources, the whole historical edifice of the Roman Empire suffers from a major structural failure, but what if other pillars of ancient historiography crumble under similar scrutiny? What about Titus Livy, author a century earlier than Tacitus of a monumental history of Rome in 142 verbose volumes, starting with the foundation of Rome in 753 BC through the reign of Augustus. It is admitted, since Louis de Beaufort’s critical analysis (1738), that the first five centuries of Livy’s history are a web of fiction. But can we trust the rest of it? It was also Petrarch, Brotton informs us, who “began piecing together texts like Livy’s History of Rome, collating different manuscxt fragments, correcting corruptions in the language, and imitating its style in writing a more linguistically fluent and rhetorically persuasive form of Latin.” None of the manuscxts used by Petrarch are available anymore.

彼特拉克发现的中世纪手稿已经失传很久了,那么除了彼特拉克的名声,我们还有什么证据可以证明它们的真实性呢?想象一下,如果历史学家认真质疑一些我们最珍视的古典宝藏的真实性。他们中有多少人能通过测试?如果Hochart是对的,塔西佗被从可靠来源的名单中剔除,那么整个罗马帝国的历史大厦将遭受重大的结构性失败,但如果古代史学的其他支柱在类似的审查下崩溃怎么办?

那提图斯·李维呢?他比塔西佗早一个世纪,写了一部142卷的罗马历史巨著,从公元前753年罗马的建立开始,一直到奥古斯都统治时期。自路易斯·德·博福特(Louis de Beaufort)的批判性分析(1738)以来,人们承认,李维的前五个世纪虚构的。但我们能相信剩下的吗?也是彼特拉克,布罗顿告诉我们,他“开始拼凑像李维的《罗马史》这样的文本,整理不同的手稿碎片,纠正语言中的变体,模仿其风格,写一种语言上更流畅、修辞上更有说服力的拉丁语形式。”彼特拉克使用过的手稿都没有了。

彼特拉克发现的中世纪手稿已经失传很久了,那么除了彼特拉克的名声,我们还有什么证据可以证明它们的真实性呢?想象一下,如果历史学家认真质疑一些我们最珍视的古典宝藏的真实性。他们中有多少人能通过测试?如果Hochart是对的,塔西佗被从可靠来源的名单中剔除,那么整个罗马帝国的历史大厦将遭受重大的结构性失败,但如果古代史学的其他支柱在类似的审查下崩溃怎么办?

那提图斯·李维呢?他比塔西佗早一个世纪,写了一部142卷的罗马历史巨著,从公元前753年罗马的建立开始,一直到奥古斯都统治时期。自路易斯·德·博福特(Louis de Beaufort)的批判性分析(1738)以来,人们承认,李维的前五个世纪虚构的。但我们能相信剩下的吗?也是彼特拉克,布罗顿告诉我们,他“开始拼凑像李维的《罗马史》这样的文本,整理不同的手稿碎片,纠正语言中的变体,模仿其风格,写一种语言上更流畅、修辞上更有说服力的拉丁语形式。”彼特拉克使用过的手稿都没有了。

What about the Augustan History (Historia Augusta), a Roman chronicle that Edward Gibbon trusted entirely for writing his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire? It has since been exposed as the work of an impostor who has masked his fraud by inventing sources from scratch. However, for some vague reason, it is assumed that the forger lived in the fifth century, which is supposed to make his forgery worthwhile anyway. In reality, some of its stories sound like cryptic satire of Renaissance mores, others like Christian calumny of pre-Christian religion. How likely is it, for example, that the hero Antinous, worshipped throughout the Mediterranean Basin as an avatar of Osiris, was the gay lover (eromenos) of Hadrian, as told in Augustan History? Such questions of plausibility are simply ignored by professional historians.[9] But they jump to the face of any lay reader unimpressed by scholarly consensus. For instance, just reading the summary of Suetonius’ Lives of the Twelve Cesars on the Wikipedia page should suffice to raise very strong suspicions, not only of fraud, but of mockery, for we are obviously dealing here with biographies of great imagination, but of no historical value whatsoever.

那么《奥古斯都史》(Historia Augusta)呢?这是一部罗马编年史,爱德华·吉本在撰写《罗马帝国衰亡史》时完全信任它。它后来被揭露为一个骗子的作品,他通过从头开始编造来源来掩盖自己的欺诈行为。然而,由于一些模糊的原因,考虑到伪造者可能生活在五世纪,这应该使他的伪造无论如何都是值得的。实际上,它的一些故事听起来像是对文艺复兴时期习俗的神秘讽刺,另一些故事则像是基督教对前基督世界的宗教的诽谤。

例如,在整个地中海盆地作为奥西里斯化身而受到崇拜的英雄安提努斯,有多大可能是《奥古斯都史》中所说的哈德良的同性恋情人(eromenos) ?这些问题的合理性被专业历史学家完全忽略了。但是,对于任何对学术共识不感兴趣的外行读者来说,它们都是直截了当的。

例如,只要阅读维基百科页面上苏托尼乌斯的《十二凯撒传》的摘要,就足以引起强烈的怀疑,不仅是欺诈,而且是嘲弄,因为我们显然在这里处理的是充满想象力的传记,但没有任何历史价值。

(未完待续)

那么《奥古斯都史》(Historia Augusta)呢?这是一部罗马编年史,爱德华·吉本在撰写《罗马帝国衰亡史》时完全信任它。它后来被揭露为一个骗子的作品,他通过从头开始编造来源来掩盖自己的欺诈行为。然而,由于一些模糊的原因,考虑到伪造者可能生活在五世纪,这应该使他的伪造无论如何都是值得的。实际上,它的一些故事听起来像是对文艺复兴时期习俗的神秘讽刺,另一些故事则像是基督教对前基督世界的宗教的诽谤。

例如,在整个地中海盆地作为奥西里斯化身而受到崇拜的英雄安提努斯,有多大可能是《奥古斯都史》中所说的哈德良的同性恋情人(eromenos) ?这些问题的合理性被专业历史学家完全忽略了。但是,对于任何对学术共识不感兴趣的外行读者来说,它们都是直截了当的。

例如,只要阅读维基百科页面上苏托尼乌斯的《十二凯撒传》的摘要,就足以引起强烈的怀疑,不仅是欺诈,而且是嘲弄,因为我们显然在这里处理的是充满想象力的传记,但没有任何历史价值。

(未完待续)

评论翻译

很赞 ( 10 )

收藏

原创翻译:龙腾网 http://www.ltaaa.cn 转载请注明出处